This article first appeared in Enterprise, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on December 30, 2019 - January 5, 2020

Sector: Medical devices; home-based dialysis

Addressable market: US$1.5 billion – US$2 billion, Malaysia’s annual dialysis expenditure

Intellectual property status: Pending for both MyIPO and Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications

Product description: Significantly more compact peritoneal dialysis machine

Fully automated and operable at home

Internet of Things (IoT) enabled for cloud-based data storage & telemedicine support

Currently exporting: No

Industry challenges: Lack of local key opinion leaders to drive market awareness/adoption

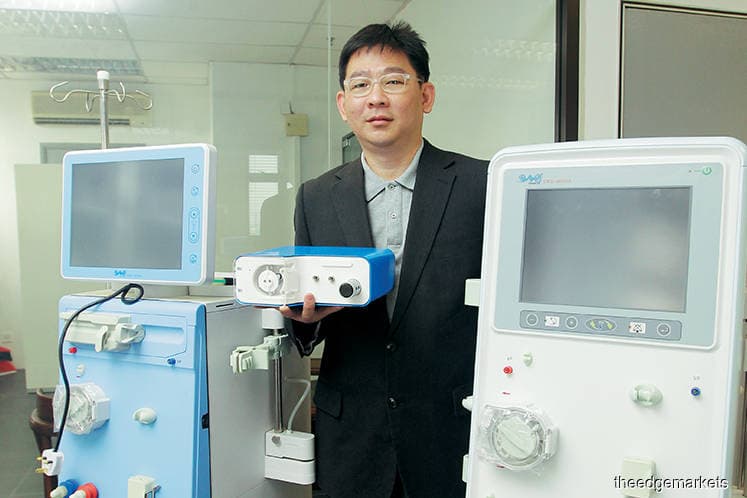

More than a year has passed since Enterprise first spoke to Medical Devices Corp Sdn Bhd founder and director Loke Khing Hong, who pioneered a revolutionary medical device — a portable, fully automated peritoneal dialysis machine. He has set his sights on manufacturing the device for both local and foreign markets despite the fact that the company is a new entrant in a market dominated by a few multibillion-dollar giants.

The prototype peritoneal dialysis machine is designed to be calibrated by the patient himself, with no additional assistance. “You hook up the machine and go to sleep. The machine will take care of everything — fill [your abdominal cavity with a special cleansing solution], dwell [allow the liquid to circulate through the body and absorb waste products] and drain several times throughout the night,” he says.

Loke has managed to make the machine more compact than ever. His prototype weighs just 4kg and comes with its own carrier bag for convenient deployment and storage.

He has made some headway since the interview last year, particularly in terms of raising a portion of the initial RM8 million that he needed to manufacture at greater scale. Now a year older and wiser, he tells Enterprise that challenges still abound.

Loke plans to shake up the multibillion-dollar medical devices market dominated by a handful of international conglomerates. Perhaps he has not taken into account just how difficult it is for policymakers and regulators to accept such an innovative solution.

To recap, the market is currently dominated by bulky haemodialysis machines. Weighing roughly 18kg and standing as tall as two stacked desktop central processing units, these machines sadly, often signify the end of a patient’s independence and productivity.

Patients who suffer from kidney failure have three options — they can get a kidney transplant (a difficult prospect owing to a lack of donors), undergo haemodialysis or opt for peritoneal dialysis.

“With haemodialysis, they go to a hospital or dialysis centre, where a tube is inserted into a vein. The blood is drained out, filtered and then returned to the body. They need to do this every other day, for four or five hours at a stretch. After that, they are usually too tired to work,” said Loke in last year’s interview.

With haemodialysis, patients — particularly the younger ones — face the bleak prospect of lifelong dialysis, quite possibly without the ability to work full-time and support a family.

Peritoneal dialysis is another option. But until recently, part of the process had to be undertaken manually, by a human operator. This is where Loke has successfully innovated the device, automating the entire process while keeping the machine compact and manoeuvrable.

Investments coming in

The good news is that in the past year, Loke has successfully acquired a little more than RM4 million from local angel investors. He still needs more than RM3 million and with the year heading to a close, he is less and less optimistic about the prospect of raising the funds locally.

Loke has since changed tack and courted potential investors from overseas over the last few months. But why didn’t he just approach foreign investors right from the start?

“I resisted making calls to international investors because it was a dream of mine to be a fully local medical device manufacturer, providing solutions to Malaysia and beyond,” says Loke.

He was initially reluctant to offer equity to international players as Malaysia had long lacked strong, locally founded (and owned) pharmaceutical and medical device brands, he adds. “Since Independence, the country has been a net importer of pharmaceuticals and medical devices. According to a report by the Malaysia Competition Commission, we import roughly US$1.1 billion in drugs alone.

“This number would be higher if we took into account important medical devices like haemodialysis machines. In fact, all the haemodialysis machines in the country are imported as the market is controlled by two major international companies.”

Sadly, this has caused the stakeholders in the local medical device ecosystem — Loke makes references to “key regulators and policymakers” — to have difficulty accepting new solutions for the market. “Because we have never really produced our own medical devices, stakeholders tend to undervalue the importance of innovation in the local healthcare scene. They do not appreciate that there is an exhaustive development process that needs to take place. They have always imported finished and fully certified products,” he says.

Initially, Loke’s strategy was to approach the public health sector — the Ministry of Health (MoH) to be specific — rather than the private sector. He reasoned that the public health sector had a much greater need for his innovation because of the sheer volume of case work and patient backlogs.

“We are at near crisis levels. Every year, we see roughly 8,000 new patients requiring dialysis, and the public healthcare system struggles to absorb even a quarter of that load. The other three quarters undergo treatment through the private healthcare sector or rely on the assistance of non-governmental organisations,” says Loke.

But he has been disappointed at the reception to his product. “I believe innovation and product development in the healthcare sector are not a particularly high priority for the government right now. To some extent, it is understandable because the ministry does have a lot of other major, pressing concerns,” he says.

“But they tend to look at themselves as just an end-user, as opposed to being a key player in the medical innovation value chain. When we approached them, they were expecting us to have a fully finished and internationally certified product.”

Loke was hoping to receive strategic support from the MoH, in particular, to run patient testing and the attendant clinical studies. He was hopeful that with the weight of the ministry behind his innovation, he would be better positioned to engage with international distributors, with a view to opening new export markets. Sadly, this has not come to pass.

Pressing on

Even so, Loke has not rested on his laurels. In addition to his efforts with the MoH, he has successfully acquired the highly regarded ISO 13485 certification for medical device management system. It gives him a valuable foot in the door in terms of his plan to export. But this is only the start of a very long journey, he says.

“The ISO certification was a win for me. But my long-term strategy is to export to the European and North American markets. To do this, I need to acquire two other certifications,” says Loke.

He is focusing his efforts on penetrating foreign markets that have policies to encourage home dialysis, which is exactly what his device allows. According to him, countries that have adopted such policies include Canada, the US, Mexico, Australia and New Zealand as well as the EU.

Loke has already decided to acquire the relevant certification that would allow him to penetrate the EU as it would give him invaluable access to a massive, highly integrated, continental market. This certification is known as the CE mark.

The CE mark would serve as the proof he needs to show distributors that his product satisfies the requirements of the European Medical Device Directives. As for the US market, he will need to apply for US Food and Drug Administration approvals. For now, he has chosen to focus his efforts on acquiring the CE mark.

But the certification is not cheap. “I know of a European competitor that spent about €500,000 (RM2.3 million) to acquire the CE mark. But we need to be as cost-efficient as possible. So, we have elected to conduct as much of the application and preparation processes ourselves,” says Loke.

He says, it is not uncommon for companies to spend hundreds of thousands on third-party consultants who, in turn, draw up highly detailed master plans for the benefit of key decision-makers later on. He is undertaking this process in-house to save costs. He has allocated a maximum of US$200,000 (RM834,236) to the entire CE mark application process.

Loke may have hit a setback in the past year, but he is more determined than ever to realise his dream of being a locally founded, medical device manufacturer and exporter. His immediate plans are to complete his first fully fledged human pilot study and then get his device approved and registered with the Medical Device Authority. If all goes well, he will get his CE mark in the next 18 months.

Loke aims to bring his product to market in the next 18 to 36 months. And if he is lucky, to multiple markets. “Over the longer term, that is, taking a five-year view, I hope we can evolve to become a full spectrum provider for peritoneal dialysis,” he says.

“By this, I mean that in addition to manufacturing and exporting the device, we also want to get into the manufacturing of various solutions that pass through the machine and circulate through the patient’s body as a means to absorb impurities and waste products.”

Save by subscribing to us for your print and/or digital copy.

P/S: The Edge is also available on Apple's AppStore and Androids' Google Play.