This article first appeared in The Edge Financial Daily, on November 20, 2015.

PRESIDENT Francois Hollande has closed France’s borders for three months after last Friday’s terrorist attacks on Paris.

But this is only the latest shutdown to threaten Europe’s coherence and unity.

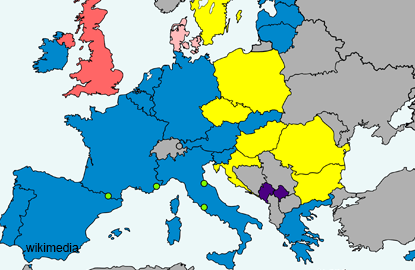

European Council president Donald Tusk warned last week of a “race against time” to save the 1985 Schengen Agreement, which created open borders among almost all members of the European Union (EU) as well as a few other countries.

That is putting it mildly. Germany, the EU’s 800-pound gorilla, closed its border with Austria in September. Even Sweden, the most welcoming European country when it comes to refugees, has implemented border checks.

The race is not to save Europe’s open borders. It is to save Europe from failing under the weight of its own contradictions.

Start with the practical side. Imagine that you needed to take a passport with you on Amtrak’s Acela from New York to Washington, and show it every time you cross a state line. That is five stops and five passport checks on the three-hour ride. The illustration dramatises the overwhelming benefit of Europe’s agreement. If you want economic integration, the movement of people across borders is one of the two most basic necessities, alongside the free movement of goods.

During the Greek crisis, it was eminently clear that the struggle between Europe’s poorer and richer countries grew from a basic tension in the EU structure. Monetary union deprives countries of the familiar sovereign tool of devaluing currency when they find themselves in a financial hole. Yet European states are (mostly) sovereign when it comes to raising taxes and spending their budgets. Germany and Greece pulled back from the brink by negotiating a bailout, but the structural problem remains.

What is undercutting the Schengen Agreement is similarly a structural problem. Open borders mean that anyone — citizen or foreigner — can cross without being checked. Countries with open borders give up a classically important piece of sovereignty, namely border controls. Those controls are not just symbolic — they matter for security and social-service delivery alike.

Yet when it comes to taking care of refugees who come into a country, the European states are largely on their own — like independent sovereigns.

The European mechanism that was supposed to solve this problem with refugees is the Dublin Regulation, which came into force in 1997 and has been amended several times since. The basic principle is that the country where a potential refugee first enters the EU is responsible for processing his or her claim to asylum. As envisioned, the agreement would have meant that potential refugees would not flow freely across Europe’s internal borders, but would stay put waiting for their asylum applications to be processed.

In practice, however, the Dublin system suffers from a basic flaw: Countries are differently situated when it comes to major refugee influxes. Hungary borders Serbia and Croatia, which are not part of the Schengen zone, so it is particularly vulnerable to economic migrants from the Balkans.

Greece and Italy have thousands of miles of Mediterranean coastline, and so can be reached from the sea. In contrast, if you are a refugee from outside Europe trying to reach Sweden, you will ordinarily have to pass through lots of other European countries unless you’re lucky enough to get on board a direct flight.

No surprise, then, that the Dublin system has basically collapsed.

So what does the EU do to rationalise the border problem in the light of the tremendous flow of human beings from Syria and, increasingly, Afghanistan?

There are several logical possibilities, each fraught with its own challenges. Richer European countries could pay for hardened borders around the whole of Europe, and eventually coordinate their protection. That would make the EU more like a single country, with unified border control. It might also have security benefits because potential refugees could be vetted before entry.

In essence, that would allow Europe to keep migrants and refugees out, which in turn would allow the free flow of EU citizens across EU borders on the Schengen model. Part of the reason you do not have to show a passport on the Acela is that you do have to show one when you enter the United States legally.

The trouble with this approach is not just the expense but also that it might not stop desperate immigrants from trying to enter, particularly from the sea. The European Court of Human Rights has held that refugees cannot be turned back once they have been brought on board European flagged vessels. Even if that ruling were reversed, it would be politically difficult for at least some European countries to turn away legitimate refugees.

A softer variant of coordinated border control is coordinated bribery of non-EU countries to keep refugees, paid for by the richer European nations. Such an effort is under way, with proposals to pay Turkey €2.5 billion (RM11.56 billion) to block its borders with Europe.

Another option for Europe is to develop a centralised, coordinated policy for distributing refugees. At present, it is been mostly up to individual European members to decide how many they can take, leading to vast disparities in absolute and relative numbers. The costs of refugees are therefore borne very unequally.

Further European integration is hard to achieve under the best of circumstances, and it would doubtless be impossible to get members states to vote voluntarily to give up the sovereign right to decide on the refugees they will take.

The upshot is that Europe’s open borders are going to disappear for at least as long as major refugee flows continue. And it will be difficult to restore them later.

In its first decade of existence, the US learned the overwhelming difficulties of coordinating 13 sovereignties into a single confederation. Only the impending collapse under the Articles of Confederation drove the country to the federal constitution. Europe is not there yet. But the contradictions of sovereigns in a union have not changed much in the last couple of hundred years. The EU will have to evolve or die. — Bloomberg View

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg View columnist.